Ketogenic Diet Reduces Seizures in Many Kids With Epilepsy

An Expert Interview With Mary Zupanc, MD

By Troy Brown from medscape

Editor’s note: The ketogenic diet was developed in the early 1920s as a treatment for epilepsy. Nobody really knows for sure how it works, but scientists believe the low glucose and ketosis that develop as a result of the diet change the metabolic pathways in the brain, reducing the frequency of seizures.

Mary Zupanc, MD, director of the comprehensive epilepsy program and chief of the division of child neurology at the Children’s Hospital of Orange County in Orange, California, discussed the ketogenic diet and medications currently being used to treat pediatric epilepsy at the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) 2012 Summer Meeting & Exhibition, held June 9 to 13 in Baltimore, Maryland.

She spoke with Medscape Medical News by phone about the role the ketogenic diet plays in the treatment of pediatric epilepsy.

Medscape: How does epilepsy in children differ from epilepsy in adults?

Dr. Zupanc: Pediatric epilepsy is completely different, with a different etiology. The causes of epilepsy can be quite diverse, but adult-onset epilepsy tends to be more related to tumors, atherosclerosis, dementia, stroke, hemorrhages, and trauma. There are genetic forms of epilepsy that present in adolescence and early adulthood, but for the most part, when adults present with epilepsy, we are much more concerned about a tumor. It would be highest in the differential.

In pediatric populations, the incidence is highest in the first year of life. Unlike in adults, tumor is not high on the list of possible causes. Instead, there could be underlying malformations in how the brain forms, neurometabolic diseases, and genetic causes, like chromosomal deletions, duplications, Down’s syndrome, trisomy 18, or a number of chromosomal abnormalities that can result in epilepsy.

In pediatrics, there are 2 main etiologic categories: idiopathic (probably mainly genetic) and symptomatic.

Many of the genetic forms of epilepsy are what we call channelopathies, where you have abnormalities in the sodium channel, calcium channel, or potassium channel that can lead to instability in the cell membrane and result in epileptic seizures.

The forms of epilepsy are different. There are age-dependent epilepsy syndromes. For example, in a young and immature brain, a large abnormality, such as lissencephaly (which means smooth brain), or a large malformation of cortical development, or a neurometabolic disease can sometimes present as early as in utero.

If it presents from 2 to 8 months of life, it can present as infantile spasms. When manifested in a young immature brain, malformations in cortical development, genetic causes, and metabolic causes will cause infantile spasms. In an older patient, the type of seizure would be different because the brain is more fully developed.

There are different causes of epilepsy, and the manifestations and types of seizures are very, very different. As a result, many of the treatments are also different.

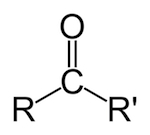

Medscape: What is the ketogenic diet, and how does it work?

Dr. Zupanc: The ketogenic diet is not a natural diet, and it is not a diet that can be done without strict medical supervision. It changes the neurochemistry of the body, and it can be associated with nausea, vomiting, lethargy, and death, just like any of the antiepileptic medications.

The mechanism of action is something nobody really understands. We know that ketosis contributes, because people who have ketosis tend not to have seizures. The combination of the low glucose and the ketosis, which changes the metabolic pathways by which the cells produce ATP — the energy source of cells — is probably involved, but the exact mechanism of action remains undetermined. There may be many different pathways that alter the metabolism of the cell and produce the effect of the ketogenic diet.

It is not a panacea, in that it rarely produces complete seizure freedom. It does result in a significant improvement in seizure control, particularly in different types of epilepsy syndromes, but families are often under the mistaken impression that it is a natural diet, that it’s something they can do at home easily, and that it will eliminate the need for antiepileptic medication.

That doesn’t typically happen. It is a type of therapy that creates an abnormal chemical state in the body that can be very effective in reducing the number of seizures. Sometimes, yes, we can simplify antiepileptic medications, but it is the rare patient who comes off all antiepileptic medications on the ketogenic diet.

Medscape: What are the indications for this diet?

Dr. Zupanc: The indications for the diet are medically intractable epilepsy, so all types of epilepsy. All types of seizures have been shown to improve, so with the ketogenic diet you can get some efficacy.

Then there are specific conditions treated with the ketogenic diet. For example, there’s a metabolic disorder called glucose transporter deficiency syndrome, where glucose can’t be transported from the blood into the cerebrospinal fluid, so these patients have low glucose in the brain. The ketogenic diet provides the ketones that allow the brain to use ketones for energy.

There are other associated disease, like pyruvate dehydrogenase complex deficiency, where the ketogenic diet is actually indicated.

Medscape: How effective is the ketogenic diet for children with intractable epilepsy?

Dr. Zupanc: It pretty much follows the law of thirds: a third will have a very significant improvement in their seizures, another third may see improvement, and in about a third of the patients, it is either not effective or the side effects become intolerable.

In one study, virtually all patients had a 50% reduction in seizure frequency and 46% remained seizure-free for more than 1 year. Over time, 33% to 35% had greater than 90% seizure reduction, 33% had a 50% to 90% reduction, and another 33% had a minimal reduction.

That’s actually pretty good for an antiepileptic drug therapy. Once you’ve failed the first 2 antiepileptic medications, the chance that a third or fourth will work is less than 5%. This kind of improvement on the ketogenic diet is notable and striking

The ketogenic diet doesn’t just stop seizures, we really think it changes a cell’s metabolism and probably the neurochemistry of the brain, so it’s antiepileptic as well as antiseizure. It may alter the synthesis or function of different neurotransmitters in the brain.

Typically, children stay on the ketogenic diet for about 2 years, and typically, we can simplify their antiepileptic medications. When we take them off the diet, seizure control is sustained. They don’t go back to seizing again. In some cases, drugs that previously were ineffective become effective after the child has been on the ketogenic diet.

There’s something more permanent about the ketogenic diet; we’re still in the process of learning lot about it.

Carl E. Stafstrom, MD, PhD, and colleagues published a study that looked at a medication that may mimic some of the effects of the ketogenic diet (Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1382-1387). Everybody would rather have a pill than have to be so restrictive about the diet in these children, but as yet we haven’t been very successful.

Medscape: What risks are associated with the ketogenic diet?

Dr. Zupanc: Some of the side effects can be pretty significant. For example, we always screen our patients for defects in fatty acid oxidation before they start the ketogenic diet, because if a child with a metabolic disorder that leads to defects in fatty acid oxidation goes on the ketogenic diet, and that child can’t metabolize fats, they can die. They become lethargic, they vomit, and they can die.

The ketogenic diet can also increase the risk for kidney stones. There are certain antiepileptic medications, such as topiramate and zonisamide, that increase the risk for kidney stones, so we always have to watch out for that in our patients.

Some children just don’t like to eat the diet. If you take a child who’s marginally fed and you put them on the ketogenic diet and they don’t want to eat and they don’t want to drink, they can get dehydrated and have problems with the ketogenic diet. With some children, if the ketogenic diet is effective but they don’t want to eat it, we actually put in a gastrostomy tube.

The biggest side effects can be, at least in the beginning, nausea, vomiting, and low glucose. As the diet proceeds, kidney stones can be a problem, particularly if they’re on topiramate and zonisamide, as can poor growth and high lipids.

Because it’s a high-fat diet, often the kids are constipated and may have an exacerbation of gastroesophageal reflux.

We do have to supplement the diet, because it doesn’t provide enough vitamin D or calcium, so patients can develop osteoporosis. They can also get other trace mineral deficiencies, so we often have to supplement the diet with calcium, vitamin D, and a vitamin supplement. Sometimes they can get acidotic, and we have to control the acidosis. That’s why they have to be under the supervision of a physician.

Medscape: What is the role of the pharmacist in the management of the ketogenic diet?

Dr. Zupanc: The pharmacist can be critical. The pharmacist has to know the glucose content of all the antiepileptic medications and other medications that the child is taking. Liquid antiepileptic medications have a lot of sugar in them, and sometimes we have to change a child’s medications to pill form. The pharmacist is the one who determines and reports the glucose content in all of the child’s medications.

The pharmacist also helps with vitamin supplementation, giving us supplements that have a low carbohydrate content. They’re an integral part of the team.

Medscape: What are some of the newly available antiepileptic medications that are being used in children, and what are their mechanisms of action

Dr. Zupanc: In infantile spasms, for example, we would use ACTH [adrenocorticotropic hormone], or possibly vigabatrin. Infantile spasms typically present in the first year of life, and are characterized by clusters of myoclonic/tonic seizures and a markedly abnormal electroencephalogram [EEG]. ACTH is an injectable medication. Vigabatrin is an irreversible GABA transaminase inhibitor, and GABA is the primary neuroinhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain, so it increases GABA in the brain. That’s one type of treatment we have for that specific epilepsy syndrome.

If we’re unsuccessful at controlling infantile spasms, many of these patients go on to develop what we call Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome, which is a combination of seizure types — tonic seizures, generalized tonic-clonic seizures, drop seizures, myoclonic seizures, and/or atypical absence seizures. It’s one of the most intractable epilepsy syndromes of childhood, and usually requires more than 1 antiepileptic medication.

Felbamate, depakote, topiramate, the ketogenic diet, lamotrigine, and rufinamide are some of the choices I would use for that specific epilepsy syndrome.

The most critical part of making a decision about therapy is not only what the seizure type is, but what the specific epilepsy syndrome is. That encompasses not only the seizure type, but the age at onset, the family history, what the EEG looks like, the neurologic exam, developmental history — a lot of things help us determine what the epilepsy syndrome is.

Determining the epilepsy syndrome will give us 2 big pieces of information. It tells us whether or not the epilepsy syndrome is likely to go into remission, and it tells us the types of antiepileptic medication that might be the most favorable and that might help us the most. There are many, many, many different epilepsy syndromes.