Chronic pain is a major issue for many people and osteoarthitis of the joints is one of the largest sources of pain that people experience. As osteoarthitis involves degeneration of the joint tissue from dystrophic calcium, aside from the recommendations outlined in the following article by Dr Mercola, reducing calcification and inflammation in the joints should be a key priority to increase your success of overcoming this chronic condition.

One of the key things to start reducing inflammation when it comes to osteoarthritis, is the proper elimination of food allergies. Food allergies are a common feature of osteoarthritic patients and need to be eliminated to increase treatment success.

If you need a good physiotherapist, consider visiting our friends at Bentall Physiotherapy. Jacek and Mariola know what they are doing when it comes to chronic pain. http://bentallphysiotherapy.com/

We specialize in the treatment of chronic pain using acupuncture, microcurrent and cold laser therapies. I will also provide injection treatments for some people, if needed.

Physical Therapy as Good as Surgery for Osteoarthritic Knees and Torn Meniscus

Originally posted on mercola.com by Dr. Mercola

Arthroscopic knee surgery for osteoarthritis is one of the most unnecessary surgeries performed today, as it works no better than a placebo surgery.

Proof of this is a double blind placebo controlled mutli-center (including Harvard’s Mass General hospital) study published in one of the most well-respected medical journals on the planet, the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM)1 over 10 years ago.

Despite this monumental finding, some 510,000 people in the United States undergo arthroscopic knee surgery every year. And at a price of anywhere from $4,500 to $7,000 per procedure, that adds up to billions of dollars every year spent on this non-beneficial surgery.

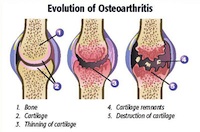

Osteoarthritis of the knee is one of the primary reasons patients receive arthroscopic surgery. This is a degenerative joint disease in which the cartilage that covers the ends of the bones in your joint deteriorates, causing bone to rub against bone.

Arthroscopic knee surgery is also commonly performed to repair a torn meniscus, the crescent-shaped fibrocartilaginous structure that acts like a cushion in your knee.

Many might think that this problem, surely, would warrant surgery. But recent research3 shows that physical therapy can be just as good as surgery for a torn meniscus, adding support to the idea that when it comes to knee pain, whether caused by osteoarthritis or torn cartilage, surgery is one of the least effective treatments available…

Physical Therapy as Good as Surgery for Torn Cartilage and Arthritis

The featured study, also published in NEJM, claims to be one of the most rigorous studies yet comparing treatments for knee pain caused by either torn meniscus or arthritis. According to the Washington Post:

“Researchers at seven major universities and orthopedic surgery centers around the U.S. assigned 351 people with arthritis and meniscus tears to get either surgery or physical therapy. The therapy was nine sessions on average plus exercises to do at home, which experts say is key to success.

After six months, both groups had similar rates of functional improvement. Pain scores also were similar.

Thirty percent of patients assigned to physical therapy wound up having surgery before the six months was up, often because they felt therapy wasn’t helping them. Yet they ended up the same as those who got surgery right away, as well as the rest of the physical therapy group who stuck with it and avoided having an operation.”

Another study, published in 2007, also found that exercise was just as effective as surgery for people with a chronic pain in the front part of their knee, known as chronic patellofemoral syndrome (PFPS), which is also frequently treated with arthroscopic surgery.

The study compared arthroscopy with exercise in 56 patients with PFPS. One group of participants was treated with knee arthroscopy and an eight-week home exercise program, while a second group received only the exercise program. At the end of nine months, patients in both groups experienced similar reductions in pain and improvements in knee mobility.

A follow-up conducted two years later still found no differences in outcomes between the two groups.

In an editorial about the featured study, Australian preventive medicine expert Rachelle Buchbinder of Monash University in Melbourne urges the medical community to change its practice and use physical therapy as the first line of treatment, reserving surgery for the minority who do not experience improvement from the therapy.

“Currently, millions of people are being exposed to potential risks associated with a treatment that may or may not offer specific benefit, and the costs are substantial,” she writes. “These results should change practice. They should also lead to reflection on the need for levels of high-quality evidence of the efficacy and safety of surgical procedures similar to those currently expected for nonoperative therapy.”

Placebo Surgery Works as Well for Osteoarthritis as Arthroscopic Surgery

Buchbinder points out the importance of sham surgery to determine the true value of operative treatments. Unfortunately, many surgeons are reluctant to take on such research. Many doctors consider them unethical because patients could undergo risks with no benefits. But it has been done. The study I mentioned at the start of the article that was published in 20028, evaluated arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis. A total of 180 participants were randomly assigned to either have the real operation or sham placebo surgery in which surgeons simply made cuts in their knees.

Those in the placebo group received a drug that put them to sleep. Unlike those getting the real operation, they did not have general anesthesia to avoid unwarranted health risks and complications. In the end, the real surgery turned out to be no better at all, compared to the sham procedure. According to the authors:

“At no point did either of the intervention groups report less pain or better function than the placebo group. For example, mean scores on the Knee-Specific Pain Scale were similar in the placebo, lavage, and débridement groups… at one year [and] at two years… Furthermore, the 95 percent confidence intervals for the differences between the placebo group and the intervention groups exclude any clinically meaningful difference.

In this controlled trial involving patients with osteoarthritis of the knee, the outcomes after arthroscopic lavage or arthroscopic débridement were no better than those after a placebo procedure.”

Outcomes in Tennis Elbow Significantly Improved by Novel Therapy

People suffering from chronic tennis elbow may also want to consider the alternatives to arthroscopic surgery. According to the largest multi-center study to date on the use of platelet rich plasma (PRP) treatment for lateral epicondylar tendinopathy (“tennis elbow”), 84 percent of patients reported significantly less pain and elbow tenderness at six months following the treatment, compared to those who received a placebo.

If You Have Joint Pain, Exercise is an Important Must

The notion that exercise is detrimental to your joints is a misconception, as there is no evidence to support this belief. Instead, the evidence points to exercise having a positive impact on your joint tissues — if you exercise sufficiently to lose weight, or maintain an ideal weight, you can in fact reduce your risk of developing joint pain due to osteoarthritis rather than increase your risk. Exercise can also improve your bone density and joint function, which can help prevent and alleviate osteoarthritis (a major cause of joint pain) as you age.

For example, previous research10 has shown that people with rheumatoid arthritis, which causes joint pain, stiffness and deformities, who did weight training for 24 weeks improved their function by up to 30 percent and their strength by 120 percent. Unfortunately, many with joint pain are missing out on these potential benefits. Research11 published in 2011 found that over 40 percent of men and 56 percent of women with knee osteoarthritis were inactive, which means they did not engage in even one 10-minute period of moderate-to-vigorous activity all week…

Exercise, along with a healthy diet, can help you to jumpstart weight loss if you’re overweight, and this can lead to tremendous improvements in your joint pain. According to a 2012 article by Harvard Health Publications:

“Each pound you lose reduces knee pressure in every step you take. One study13 found that the risk of developing osteoarthritis dropped 50 percent with each 11-pound weight loss among younger obese women. If older men lost enough weight to shift from an obese classification to just overweight — that is, from a body mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher down to one that fell between 25 and 29.9 — the researchers estimated knee osteoarthritis would decrease by a fifth. For older women, that shift would cut knee osteoarthritis by a third.”

Special Considerations for Exercising With Joint Pain

There are some factors to consider, particularly if your pain worsens with movement, as you do not want to strain a significantly unstable joint. Pain during movement is one of the most common and debilitating symptoms of osteoarthritis, and typically this is the result of your bones starting to come into contact with each other as cartilage and synovial fluid is reduced.

If you find that you’re in pain for longer than one hour after your exercise session, you should slow down or choose another form of exercise. Assistive devices are also helpful to decrease the pressure on affected joints during your workout. You may also want to work with a physical therapist or qualified personal trainer who can develop a safe range of activities for you. Your program should include a range of activities, just as I recommend for any exerciser. Weight training, high-intensity cardio, stretching and core work can all be integrated into your routine.